The Fed Cut Interest Rates Again — Here’s What It Means for Mortgages, Credit Cards, Auto Loans, and Savings

The central bank’s third consecutive rate cut is beginning to reshape borrowing costs across the economy — from mortgages and car loans to credit cards and high-yield savings accounts.

Connect with us on our social pages on Instagram TheMarketDispatch , on X TheMRKTDispatch or on LinkedIn TheMarketDispatch

The Federal Reserve lowered its benchmark interest rate by 0.25 percentage points at its final policy meeting of the year. This takes place in contrast with high stock market valuations into November and December of this year and technology stocks that have analysts wondering if we are in the middle of an AI bubble.

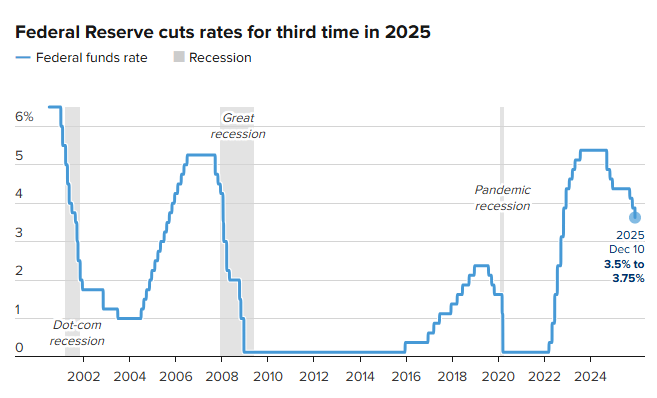

The decision marked the central bank’s third consecutive rate cut, bringing total reductions since September to 0.75 percentage points and leaving the federal funds rate in a range of 3.5% to 3.75%. In October it was hovering around 3.875%.

Those changes are expected to ripple through the economy, influencing the borrowing and savings rates faced by households.

Federal Reserve Rates from 2000 through 2025. Source: CNBC

While the federal funds rate—set by the Federal Open Market Committee (which finally received some key economic reports after the government shutdown ended) —governs the interest rate banks charge one another for overnight loans rather than what consumers directly pay, changes to that rate still shape borrowing costs across the economy.

Many short-term consumer interest rates move in tandem with the prime rate, which generally sits about three percentage points above the federal funds rate. Longer-term rates, meanwhile, are also affected by inflation expectations and broader economic conditions.

Together, these dynamics mean the Fed’s latest rate cut could influence everything from credit cards and auto loans to mortgages, student debt, and savings yields.

The Interest Rate Cut Effect on Mortgage Rates

Mortgages represent the largest source of debt for most U.S. households, but long-term home loans tend to be less sensitive to changes in Federal Reserve policy. Rates on 15- and 30-year mortgages track Treasury yields and broader economic conditions more closely than the federal funds rate itself.

With the 10-year Treasury yield climbing amid concerns about stubborn inflation, mortgage rates have followed suit. The average rate on a 30-year fixed mortgage has inched higher to roughly 6.35%, according to Mortgage News Daily as of December 9.

“Because mortgage rates are benchmarked to 10-year yields, it’s possible to see borrowing costs rise even after a rate cut,” said Brett House, an economics professor at Columbia Business School, pointing to how financial markets and investors respond to policy shifts.

That said, most homeowners carry fixed-rate mortgages, meaning their interest rate remains unchanged unless they refinance or purchase a new home.

Other types of home borrowing are more directly affected by the Fed’s moves. Adjustable-rate mortgages and home equity lines of credit are typically tied to the prime rate. While most ARMs reset annually, HELOC rates adjust almost immediately, allowing some borrowers to benefit more quickly from lower rates.

How a Fed rate cut could affect new car loans

Auto loans, like mortgages and credit cards, account for a meaningful portion of household spending. However, because most auto loans carry fixed interest rates, existing borrowers will not see their payments change as a result of the Fed’s latest cut.

Buyers who are currently shopping for a vehicle, though, may see some relief as borrowing costs ease. The average interest rate on a new car loan has declined to about 6.6%, according to Edmunds.

Even so, affordability remains strained. “Car shoppers are still navigating a difficult market, marked by record-high monthly payments and record loan balances on financed new-vehicle purchases,” said Joseph Yoon, a consumer insights analyst at Edmunds.

Data from Edmunds show that while the average annual percentage rate on new vehicles edged lower in November, the typical monthly payment climbed to a record $772. At the same time, the average amount financed for a new car reached a new high, approaching $44,000.

How Fed rate cuts influence credit card interest rates

Most U.S. adults hold at least one credit card, and many carry balances from month to month, leaving them exposed to interest rates that often hover around 20% annually on revolving debt.

Because credit card rates are variable, they are closely tied to the Federal Reserve’s benchmark rate. When the Fed lowers rates, the prime rate typically falls as well, and card APRs generally adjust within one or two billing cycles.

While a single quarter-point cut may offer limited relief given how elevated credit card rates remain, the cumulative impact of multiple reductions can become more meaningful over time—particularly compared with last year’s record-high borrowing costs, said Matt Schulz, chief credit analyst at LendingTree.

“Taken together, those cuts could translate into hundreds of dollars in savings for borrowers,” Schulz said.

Why savings rates tend to decline after Fed rate cuts

For savers, the Fed’s easing cycle makes it increasingly important to stay proactive. While the central bank does not directly set deposit rates, yields on savings accounts generally move in line with changes to the federal funds rate.

Following the Fed’s recent cuts, the highest-yielding online savings accounts are now offering rates closer to 4%, down from nearly 5% a year earlier, according to Bankrate.

“Savings rates are going to continue drifting lower,” said Stephen Kates, a certified financial planner and financial analyst at Bankrate.

For savers who rely on high-yield accounts to meet a targeted return, that environment requires closer attention, Kates said. One potential option is locking in a longer-term certificate of deposit. While the average one-year CD pays about 1.93%, the top available rates exceed 4%, according to Bankrate.

“If you find you’re no longer keeping pace with inflation, that’s a clear signal it may be time to act,” Kates said.

Disclaimer:

The information provided by The Market Dispatch is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as financial, legal, or investment advice.

The Market Dispatch, its authors, and contributors are not financial advisors, brokers, or attorneys. Any opinions, analyses, or projections expressed are solely those of the authors and do not constitute specific recommendations for any individual.

Investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal and capital. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Before making any financial decisions or investments, you should consult with a qualified financial advisor or other professional who understands your personal circumstances.

By reading this newsletter or using any related materials, you acknowledge and agree that The Market Dispatch and its team will not be held liable for any loss, damage, or expense incurred as a result of reliance on the information provided.